Fermentation and Civilization are Inseparable – John Ciardi, American Poet (1916-86)

Sake is the indigenous and traditional alcoholic beverage of Japan. Over 2000 years of culture and tradition encapsulated in a delicate sip. Sake’s roots are traceable to ancient times long before the Samurai, specifically, back to the 8th Century during the Nara Period in Japan. It was first brewed thousands of years ago as a sacred offering to the gods. The theory being that by consuming sake one could become closer or better communicate with the various deities. Today, Sake still serves a prominent role in celebratory functions, however, it is no longer confined just to special occassions and its consumption has become very much a part of everyday life. In both joy and sorrow, the Japanese lift their glasses, “kampai.”

In terms of tasting and evaluating sake, the key element to discern is the overall sense of a sake’s balance. We often refer to balance as how well the sake presents or touches the 5 tastes through a combination of its aromatic properties as well as how its flavor is perceived on the palate.

Perhaps it is helpful when enjoying sake to focus on five distinct stages: aroma (orthonasal), initial impression on the palate, textural impression on the middle palate, the finish and the retronasal sensation.

Generally, when considering the polishing grades; the higher the polishing rate, we can expect the sake to be more aromatic and nuanced, while the lower the polishing rate, the more full-bodied and straight-forward the sake will be; that said, as with everything there always tends to be more exceptions than hard fast rules.

Other Considerations:

Perishability:

Sake is a perishable item that is sensitive to light and heat.To get the longest shelf-life out of your sake, it should be refrigerated; in a retail case cooler-refrigeration scenario, with fluorescent light exposure daily, you should be able to get 3-6 months shelf-life out of sake.Fluctuations of light and storage temperature will cause sake to spoil quickly.How to tell if sake has changed?COLOR.The color will yellow and then brown.Color change does not always indicate spoilage, there is a market for aged-sake, but in general, if the color has shifted drastically, its unsaleable.

Pricing Points:

Sake is a limited small batch production commodity.It is a handcrafted brew that is very labor intensive.Ingredients are premium and fluctuations in crop yield affect pricing.Additionally, sake has to travel halfway around the world via temperature controlled container in shorter term intervals.Premium price justification can be made considering higher alcohol percentage and taxation requirements.

Sake versus Wine: Conceptually:

Wine has vintages and annual yields that can fluctuate in quality; some vintages being “more desirable,” or “better,” than others.This is a result of the culmination of particular set of environmental factors.

In contrast, the overriding objective of the sake brewmaster (toji) is to ensure that regardless of these environmental factors, the sake is consistently produced year after year.This results in sake that is identical if not better than the previous year’s.The toji therefore must tweak the recipe to offset a particular annum’s environmental factors.

Junmai Dai-Ginjyo – indicates that the sake was produced using rice milled to at least 50% of its original size. This category is considered the pinnacle of the brewer’s craft. Sakes in this category tend to be the most nuanced focused on heavily aromatic floral and fruit components and showcasing the oft delicate and subtle fruit esters capable of being coaxed out in the brewing process.

Junmai Ginjyo – indicates that the sake was produced from rice milled to a least 60% of its original size. Hallmarks of this grade of sake are a moderate-to-light body, elevated aromatics, (floral, fruit, or both) nuanced layering of flavors,

Tokubetsu Junmai – often technically qualifies as Junmai Ginjyo, however tends to lean more towards the characteristics of Junmai rather than Junmai Ginjyo. Tokubetsu translates to special, and this indicates that a special element was incorporated into the production process for the particular sake. This special process does not need to be unique to industry-wide practice, just that it be special in the course of the brewery’s production. Tokubetsu Junmai expressions typically showcase more body and flavor nuances over elevated aromatics.

Junmai – indicates two important characteristics; (1) sake free from fortification; (2) sake produced from rice milled to at least 70% of its original size. This second meaning was formerly mandated by legal regulation but has since been officially abandoned but largely adhered to industry-wide. Typical characteristics of this grade are elevated savory-ness, a noticeable structure and a full-bodied rice-forward flavor.

Rice Polishing / Washing / Steaming:

Sake production begins with raw rice. The polishing process removes the outer husk and bran of the grain. The outer layers are milled to the desired rate or semuaibuai. These layers contain proteins and fats, which may interfere with the desired flavor objective for the sake. Once polished, the rice it is washed to remove the rice flour that results from polishing. Once washed, the rice is soaked for set intervals to achieve a desired water absorption rate such to prepare the rice for optimal steaming. These intervals are adjusted according to the quality of the year’s rice harvest and to account for any changes to the weather or climate or any host of other variables suspected to affect the production process. Once the rice achieves the desired water absorption, the rice is drained and then steamed to specification.

Koji Production:

The steamed rice is then transported and stored in a room called the koji-muro. A room designed specifically to aid in the process of producing koji rice. The room is sealed and monitored for temperature, air circulation and humidity within strict parameters such to produce the most optimal conditions for producing koji rice. The steamed rice is spread out on long tables. Once spread out, the enzyme-catalyst, a friendly koji mold (aspergillus oryzae) will be sprinkled over the rice in order to affect saccharification of the starches within the rice. Over the course of a few days this friendly koji mold penetrates the rice and converts the starches into fermentable sugars.

Shubo / Yeast Starter / Mash:

Once the koji is prepared it is mixed in a small batch with pure yeast, steamed rice, and water. Over course of a couple weeks, the yeast begins to propagate resulting in a high concentration of yeast cells oft referred to as a yeast colony. At this juncture, lactic acid is added to protect the living yeast from being affected by harmful bacteria. Once the starter is ready, it is moved to a larger tank whereby 3 successive additions of rice, water, yeast and koji rice are added to the main mash over the course of 4 days ultimately doubling the batch at each addition. Upon completion of the additions, the mash is left to ferment for the next few weeks. Regular mixing and variables including temperature of the mash are monitored and adjusted accordingly. The mash ferments in a process called double parallel fermentation whereby the koji is converting the rice starch into fermentable sugars while simultaneously, the yeast consumes the fermentable sugars to produce alcohol. The mash completes fermentation under careful watch by the brewmaster over the course of next next few weeks.

Pressing / Pasteurization / Charcoal Filtration:

Once the fermentation process is complete, the mash must be pressed in order to separate the alcohol from the remaining rice solids known as lees. The pressing is typically accomplished via a pressing machine, however, other methods such as manual applied pressure using a wooden vise-like device or utilizing canvas bags to allow graviity to draw (shizuku shibori) the sake from the solids are still in use today. After tempering the sake for a few days to allow further sediment to settle, the sake may undergo pasteurization to arrest any remaining active enzymes or bacteria in order to stabalise the sake. Once pasteurized, the sake may be passed through a charcoal filter to remove unwanted colors or to adjust the flavor.

Maturation / Blending / Bottling / Second Pasteurization / Shipping:

Once the above steps are complete, the sake will be matured for several months either in a sealed tank or bottle-conditioned. At the completion of the maturation period, the sake may be blended down with water to lower the alcohol percentage. After blending, the sake will be bottled and thereupon may undergo a second pasteurization. After which the bottles will be labeled and boxed for dispatch throughout the world.

Genshu – indicates the absence of water-blending in order to lower the alcohol content of the sake; this term’s appearance on a label signifies that the sake is the full alcohol content of the fermentation. Conceptually akin to the term cask-strength.

Kimoto – a traditional production method that involves open air manual mixing of the sake mash with wooden oars allowing for comingling of the sake yeast with the natural airborne yeasts within the brewery. What results is a hybrid yeast that yields a more robust and funkier flavor profile.

Muroka – non-charcoal filtered; sake tends to be to be slight-to-moderately hued upon production and brewers rely on charcoal filtration in order to remove the hue and perceived off-flavors. The process of charcoal filtration while successful at removing these perceived flaws also tends to remove some flavor character.

Nakadare – a bottling of the middle third of the pressing process. Often considered the portion of pressing that produces the best sake.

Namachozo – indicates that the sake has only been subject to pasteurization after bottling. Literally meaning “stored raw” the sake is left to temper in storage unpasteurized in order to allow for further development of flavor and character.

Namazume – indicates that the sake was pasteurized at the tank stage but not pasteurized a second time after bottling.

Nama or Namanama – signifies the absence of pasteurization occurring in the production process entirely. These sakes tend to be the most fresh and lively as the enzymes and yeast are left active in the bottle. Sakes designated nama or namanama are highly perishable and singificantly less shelf-stable.

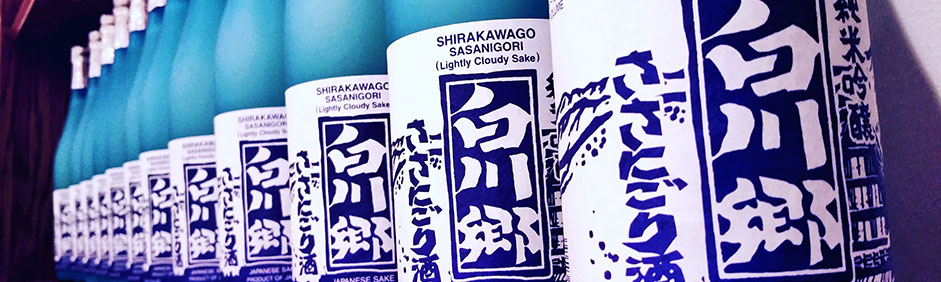

Nigori – this designation means cloudy and the sake will be visually cloudy or opaque. This characteristic is achieved at the pressing stage whereby the mash is pressed through a looser weave allowing for less and sediment to pass through into the final product. This term can be further narrowed by adding Sasa– meaning medium or moderate or Usu– meaning light or thin.

Pasteurization – is implemented to stop the enzyme and yeast activity and to stabilize the sake. Sake not designated otherwise will have been pasteurized twice in the production process. The first time is generally at the completion of the sake brewing process prior to bottling or storing. The second time occurs after bottling and prior to shipping out.

Shizenmai – sake rice that is cultivated without the use of pesticides or chemical fertilizers; oft-likened to biodynamic or natural wine production methods. The term translates to natural rice.

Shizuku-shibori – gravity-draw; allowing gravity to draw out the sake from a mash. Only the liquid that drips due to the pull of gravity is bottled and labeled as shizukushibori.

Yamahai – a result similar to that of the kimoto production method that takes about a month to produce, requiring a higher mash temperature and the addition of water, without involving manual mixing.